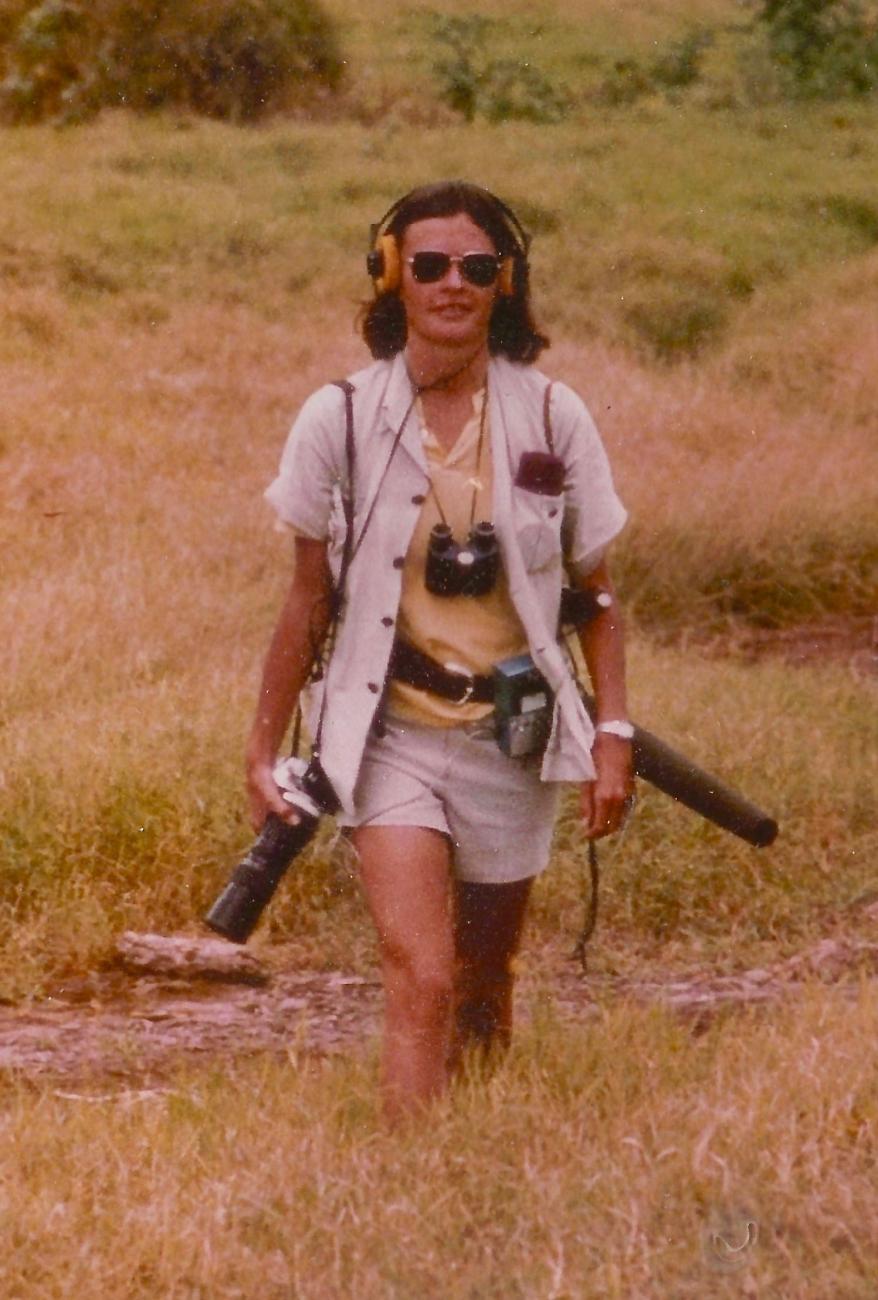

Dorothy Cheney, professor emeritus and world renowned primatologist in the department of biology in the School of Arts & Sciences at Penn, died on November 9 at her home in Devon, PA after several years’ treatment for breast cancer. She was 68.

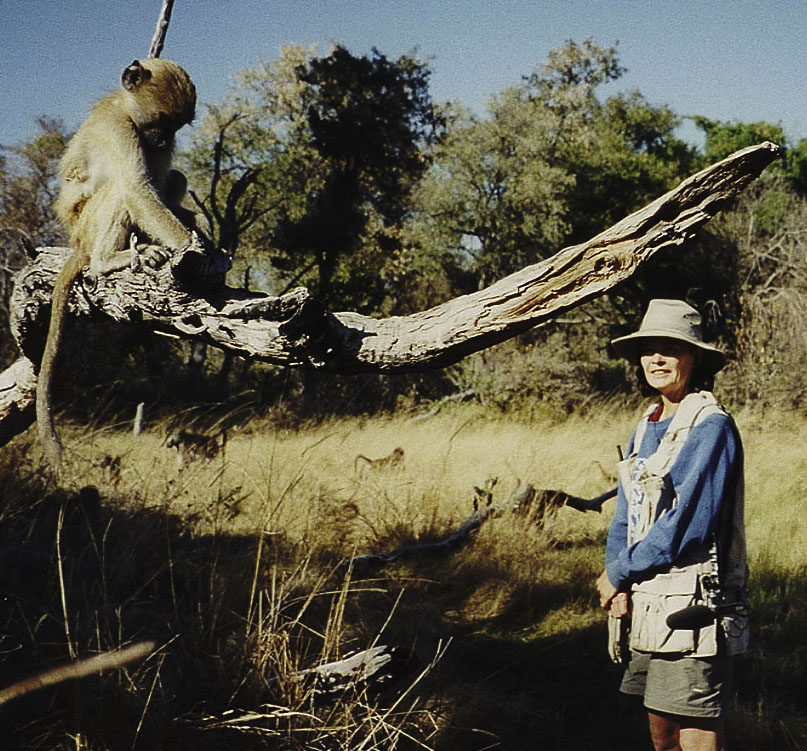

Dr. Cheney earned her bachelor’s degree in political science from Wellesley College in 1972, a year after she married to her lifelong friend, husband and colleague, Robert Seyfarth, a Professor in the department of Psychology also in the School of Arts & Sciences at Penn. Together with Robert, they went on to revolutionize the way primate field work would be done by combining careful observations with elegantly crafted controlled experiments under often uncontrolled and sometimes dangerous settings. Their work on vervet monkeys and then later on baboons provided new insights into the primate mind, and transformed how we now come to understand the evolution of social relationships. Their work provided key insight into the adaptive importance of being able to navigate the complex web of differentiated social relationships on reproductive and survival benefits. In addition to the many papers they authored together, Dorothy and Robert also wrote several books including the highly acclaimed “Baboon Metaphysics: The Evolution of a Social Mind” in 2007. For her work, Dorothy was recognized by innumerable honors. These included a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1995, election as a Fellow to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1999, election to the National Academy of Sciences in 2015, and the Distinguished Primatologist Award from the American Society of Primatology in 2016.

Dorothy’s path as a world renowned field biologist was an unusual one. After graduating with a major in Political Science, she decided to follow Robert to Cambridge University, figuring that a few years doing field work might be fun before starting law school. She then became fascinated with the field work and decided she wanted to pursue a PhD in animal behavior, or ethology as it was known in Europe. Of course since she had no background, Robert Hinde, then Royal Society Research Professor and Robert’s mentor at Cambridge University, agreed to give her a one year trial period on the condition that she write one essay each week on areas of animal behavior that he would choose. Following her PhD in zoology at Cambridge in 1977, Dorothy and her husband then moved to Rockefeller University in New York to study with Peter Marler before joining the faculty at the University of California, Los Angeles in 1981. They both moved to the University of Pennsylvania in 1985.

Dorothy will always be treasured for her sparking conversation, sardonic wit and intellectual brilliance as well as her uncanny ability in one sentence to identify both the exceptional and the mundane in any experiment, idea, or scientist. She left behind an academic lineage of highly talented and influential scientists who are now scattered across the globe at some of the most prestigious institutes and who will freely admit that she and Robert completely determined their life and career. In addition to her science, Dorothy also influenced generations of undergraduates at Penn with the popular animal behavior class she taught with Robert. Her skills as a teacher were recognized with a teaching award in 2009. As a teacher, she was a kind and thoughtful professor who was willing to share her time and intellect with her students. But just as she was known to be unflinchingly self-critical and rigorous in her work and writing, she also taught her students the value of exhibiting that same level of critical thinking.

Dorothy’s departure was much too early and there is so much more that she could have taught us. She was able to provide scientific rigor to what she would term “squishy” questions by designing truly ingenious experiments that provided a glimpse into how monkeys see the world. Together with Robert, her scientific method generated a culture of how science should be done in the field by developing a research method that allowed experimental control without sacrificing ecological validity. To paraphrase one of her students, Dorothy showed all of us in life the virtues of modesty, sincerity and honesty. In many ways her biggest scientific accomplishment were to describe the primate mind, as it had never been done before – with modesty, sincerity, and honesty.

Publications are listed at our Baboon Research web site.